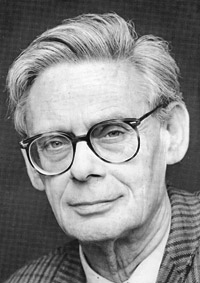

In memoriam Em Prof Erik Zürcher, 1928-2008

- On Thursday 7 February 2008, the first day of the Chinese New Year,

Emeritus Professor Erik Zürcher passed away. He had been in frail

health for some time, and his eyes were giving him trouble. He remained

fully clear of mind until the end, as testified by his publication in

2007 of a major monograph containing translations of conversations

between Jesuit Guilio Aleni and local Chinese literati. This constitutes

a unique study of international religious contact, for once not

focusing on polemics conducted from elite perspectives but on debate

between a missionary and what Zürcher liked to call the local

schoolmasters.

A student at Leiden University from 1947, Erik Zürcher produced a

brilliant PhD dissertation in 1959, which quickly became a classic in

the study of Chinese Buddhism, The Buddhist Conquest of China. The first edition is still graced by his beautiful Chinese handwriting (he was also known for his masterful drawings). The Buddhist Conquest

was reprinted in 1972 and again in 2007, indicating the importance of

this work. Personally, I have always felt that his dissertation must

have been both a joy (for it set him off on a successful career) and a

burden (for it was a hard act to follow). Be that as it may, he wrote a

flow of serious articles from the 1970s onward – on such topics as early

Chinese vernacular, Buddhist messianism and the early Jesuit mission –

of which the significance is undiminished today. Somewhere hidden in a

drawer there must be several typescript chapters of his grammar of the

Chinese in Kumarajiva’s translations of Buddhist texts. A common element

in his research on Buddhism, Christianity and Chinese communism was the

encounter of Chinese culture and foreign thought and worldviews.

Characteristically, while he produced a course syllabus containing a

detailed analytical model for this material, he never published this in

English. He often preferred staying close to the sources rather than

designing abstract vistas.

In addition to his scholarly work, Zürcher was also a builder of

institutions, at a time when there was much room for personal initiative

without red tape or formats imposed from above. As early as 1931,

Zürcher’s teacher, Professor JLL Duyvendak, had founded the Sinological

Institute; after Professor Hulsewé retired in 1974, Zürcher became the

Institute’s director, even though the directorship was later deemed ad interim,

because the Institute’s formal status had somehow evaporated between

institutional-organizational lines. However, since “the Sinological

Institute” is how Chinese Studies at Leiden University was known

internationally, we have continued to use this name at home and abroad –

and with some justification, for the Institute comprises a Department

of Chinese Studies and an outstanding Sinological Library.

Having first been appointed Reader, in 1961 Erik Zürcher took up duty as

full professor of Far-Eastern History, with special attention to

Chinese-Western contacts in the broad sense. This was doubtless a

purposefully vague designation: in the Chinese tradition, the West

includes India, the breeding ground of Buddhism, and not just faraway

Europe. In 1969, after several years of successful lobbying, Zürcher

founded the Documentation Center for Contemporary China (with a

dedicated budget), facilitating the study of present-day China and

communism by others. In Europe, this made Leiden one of the Universities

that took modern China seriously early on. In itself this made sense,

since Chinese Studies in the Netherlands had consistently been linked

with practical concerns in the areas of colonial rule, international

relations and trade – but it was typical of Zürcher that he managed to

put the study of modern China on an institutional footing. From 1976 to

1992, he was co-editor of T’oung Pao, the oldest still extant

sinological journal today. He enjoyed ample academic recognition,

visible in honors such as membership of the Royal Netherlands Academy of

Arts and Sciences (from 1975) and election to Correspondant étranger de

l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-lettres (from 1985).

From the 1970s, while taking part in work on European Expansion

elsewhere in the Faculty of Arts, Zürcher taught and served in various

administrative functions in the Department of Chinese Studies.

Additionally, throughout the years he sat on countless committees inside

the University and elsewhere, including international scholarly

organizations and institutions such as Unesco. In 1978, following a

request from Chinese Studies’ students, he began preparing slide series

for classroom use, an initiative which quickly grew into a prestigious

project for visual education (co)funded by the Taiwan Chiang Ching-kuo

Foundation, for which, together with colleagues, he systematically

collected images for the production of thematic slide series. The

project moved on into computerization early on, but following the

increasingly strict enforcement of copyright rules and the advent of the

Internet, what had been a head start now turned into an administrative

backlog that made it difficult to continue and expand. Meanwhile, many

cohorts of students had enjoyed and learned from this “visualization of

Chinese history”. Zürcher’s interest in matters visual, closely

interwoven with the archaeology, art and material culture of China, was

also manifest in his initiative toward the establishment of the

Hulsewé-Wazniewski Foundation, which has advanced teaching and research

in these areas at Leiden University since 1997.

As in his research, so in his teaching Zürcher excelled at clear,

well-formulated exposition. Unfortunately, he had no senior students in

his own, original field of early Buddhism, but he trained many in the

study of Christianity in China in the 17th century. Especially his 1980s

seminars truly helped shape some of his students at the time, including

Nicolas Standaert, now professor of Chinese at the Catholic University

of Leuven and the undersigned. Still, personal attention was not the

most important thing, for Zürcher was used to maintaining a certain

distance from us as students, and later as PhD candidates and

colleagues. While this could at times be frustrating, it was more than

made good by the sheer space he gave us to develop – and this was not

just laissez-faire but also bespoke a fundamental conception of

and attitude to knowledge. During seminar sessions, he would, for

instance, emphasize that he himself had needed years to master

particular types of language such as those employed in Buddhist and

Taoist texts. At the same time, frequent instances of irony in his

comments on our readings created room for new interpretations. His

astonishing command of various types of premodern Chinese (and English,

and Dutch, and many other tongues) made what he said highly motivating

for me and many others.

Erik Zürcher combined phenomenal erudition with an exceptionally

critical mind and something one might simply call intellectual style –

and with a keen sense of humor. He was a great sinologist, who made

invaluable contributions to scholarship and inspired many students and

colleagues.

Barend ter Haar, 12 February 2008

---------------------------

Caption: Erik Zürcher in 1991

Leonard Blussé and Harriet T Zurndorfer (eds), Conflict and Accommodation in Early Modern East Asia: Essays in Honor of Erik Zürcher, Leiden: Brill, 1993